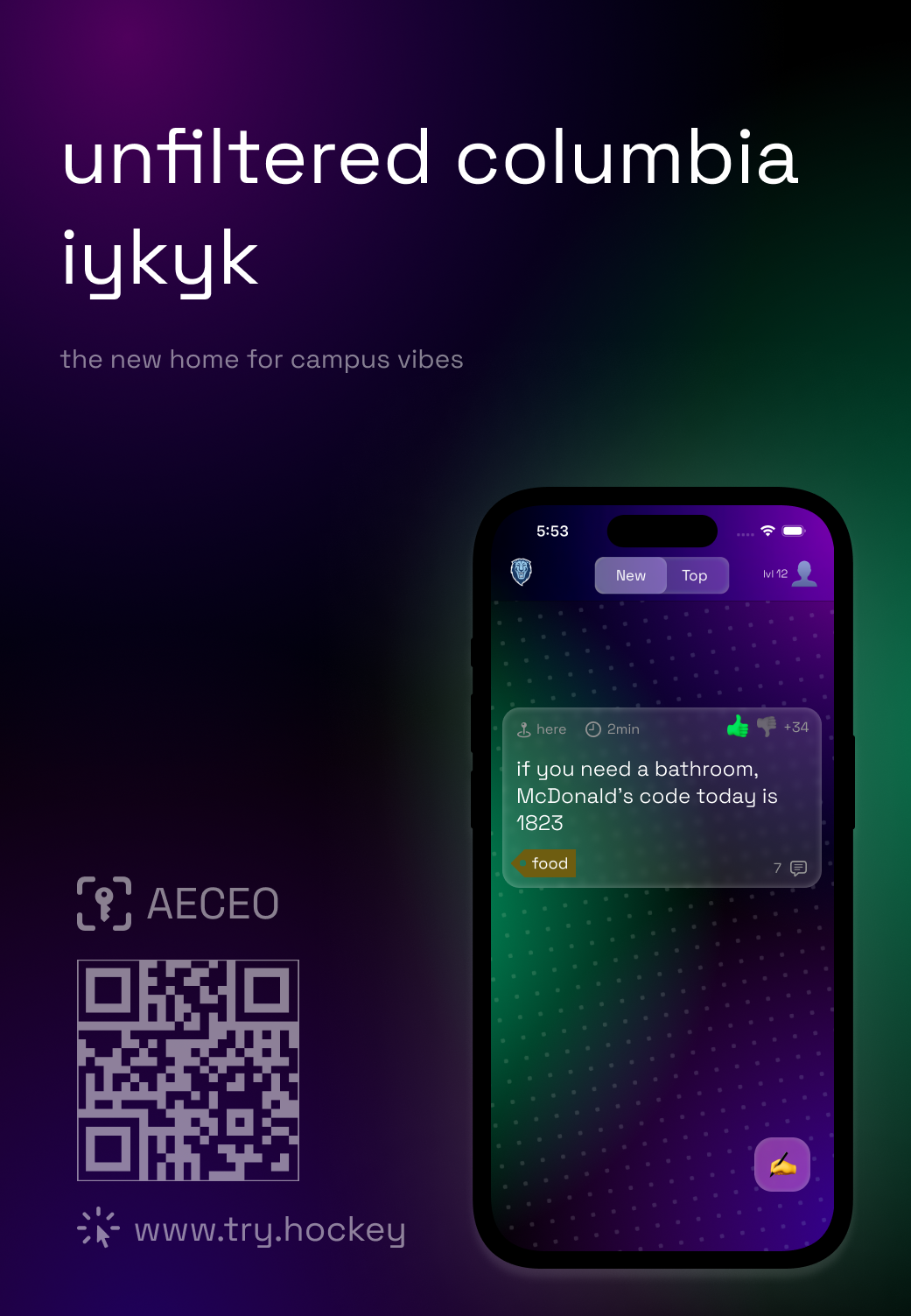

After the Hockey Messenger, I built another product called Hockey. Nicknamed “hyperlocal,” the Hockey Campus App was a modern spin on Yik Yak.

I always pitched Hockey as Yik Yak 3.0. Why 3.0 and not 2.0? I attributed the interim step to Jodel. A German social app whose founder I first met in 2020.

Yik Yak

Yik Yak was an app in 2013. It was the golden age of consumer social. They pulled all the stops and launched their campus-based social app with a bus, an electric Yak that people could ride, and branded socks. Peak 2013. The app was a school-focused clone of Twitter that came with two twists: 1. You could only see posts from people within a campus-sized radius, about 1 mile. 2. Everyone was anonymous, and there were no accounts or usernames.

This unique combination of features fostered a community with plenty of inside jokes and a tight-knit community with content that mattered to you personally. With only users from your college, it felt like a never-ending online frat party where people exchanged the latest gossip and talked about topics uniquely relevant to your campus.

Soon, Yik Yak spread to high schools, marking the beginning of its end. High school students proceeded to create an air of hostility, gossip, and bullying that drove users suicidal in more than one case. The controversy over the app grew to the point where many schools banned the app from their premises, and teachers and parents protested against its very existence. Yik Yak eventually shut down, unable to make the platform a safe space for its users.

Jodel

At the same time Yik Yak launched, the German entrepreneur team around Alessio Borgmeyer was traveling and learning about entrepreneurship abroad in the U.S. They were working on a social app called tellM. Inspired by Yak Yak’s success, they took the same concept back to Germany and started the app Jodel.

I started college in 2014, the same year Jodel launched. I was a user from day one and got hooked on the app. It felt like a unique combination of banter, news, and community I had never seen before or since. It was a special place. The added spice of anonymity, the knowledge that all of these people on the app live close to you, and the knowledge that you might be talking to one of your real-life friends without realizing it made the app fun and addictive.

Jodel solved Yik Yak’s most significant issue by introducing moderators. It’s a Stack Overflow-like system in which content creators who receive upvotes and positive feedback from the community get rewarded with access to moderation features. The app tricks active users into performing free labor for the platform. Many users talk about the moderator status and the power it brings with it, and there is an air of exclusivity around them.

I believe that this moderation feature was Jodel’s most significant innovation. They were also keen to establish the app as 17+ and only allowed non-college students to sign up about five years after launch. These factors might’ve aided Alessio and his team in creating a lasting product, while their U.S. role model, Yik Yak, had to shut down much sooner.

Hockey

These insights bring us to the pitch. I was selling Hockey to investors and anyone who might listen as a reboot of Yik Yak aided by unique insights into being a ten-year power user of Yik Yak’s little-known German counterpart. An app that fixed the U.S. app’s most significant issues and provides a playbook on how to bring a more long-lasting version of this idea to market.

The timing wasn’t a coincidence either. I was convinced that the end of the pandemic and the return to in-person learning left first-year students in a unique and never-before-seen situation. They had spent their last high school years at home, attending school virtually. These kids, robbed of two critical years of social development, were now starting college. This change is already a scary and life-changing step. These unique circumstances made it even more difficult.

College comes with so many questions that you are too embarrassed to ask. There is so much pressure to fit in, make friends, and do well at school. Things work very differently from how life was in high school. In my mind, these circumstances proved a fertile breeding ground for creating an open, anonymous, tailored community for your college and campus.

I built the first version of the Hockey Campus app in about three weeks. I deployed it on AWS Lambda, built it in SwiftUI, and added advanced features like AI profanity and nudity detection. Deploying an ML-based image nudity detection on Lambda was difficult. Still, I got there and ultimately had a fully scalable, fully self-hosted system: no SaaS, virtually free hosting.

I spent too much time building existing things from scratch on previous projects. I wrote about some of those learnings in earlier blog posts. With this project, though, I think I found a good balance. The architecture seemed maintainable, fast, and cost-efficient, and I built the whole thing in less than a month.

I spent much more time marketing this app than building it, which I’m really proud of. I learned from my mistakes and prioritized my time differently. I was putting product-market fit ahead of engineering. I designed and printed flyers, giving every one of them a unique and trackable link to analyze the performance of different designs and locations. I did the footwork and went out there to talk to people. I interviewed students on the Columbia campus for a few days straight, and I convinced a food truck owner to let me post my flyer on the side of their truck.

My perception of the Hockey Messenger then was that the product failed because of a lack of investment, which I blamed on a VC down market. So, with the campus app, my goal was to get users before fundraising. All my previous startups were set up to raise money for marketing. With the Hockey Campus app, I did marketing to raise money. I went far outside my comfort zone with this one.

The best example is that I put flyers in one of Columbia’s biggest lecture halls. I researched which lecture halls were used by large first-year classes and picked one with interdisciplinary topics that students of many majors attended. I set an early alarm and waited outside the door of the campus building to sneak in behind someone with a keycard. I went inside the lecture hall before the first class (but after the cleaning staff had left to minimize the chances of them removing the flyers) and taped my 12 flyers on the back of the chairs.

In my mind, students in interdisciplinary classes would sit there, get bored, and start paying close attention to anything that could distract them. A flyer in front of their seat should be prime real estate and generate plenty of downloads.

The Results

All this time and effort spent acquiring users didn’t work, and my crystal ball won’t give me a clear answer. This thing must be broken. I have some theories, though. After all of my efforts and guerilla marketing strategies, I think a real user has yet to post on the app once. I had set up a complicated auto-posting system that would make it look like there were about 20 people actively posting and commenting on the app. I scheduled AI-generated content and some images taken from Jodel to fill a few weeks after launching the app. Those generated posts were the only ones made on the app, however.

My first theory is that launching social apps like this isn’t a thing anymore. Back in 2014, TikTok wasn’t a thing, and if you wanted to waste time on your phone, you had to look up things to do actively. Now, you can scroll on TikTok for as long as you want, and there will always be a content supply. You can fill up an uncapped amount of screen time, and you’re not yearning for new ways to distract yourself. There are already at least five apps on your phone that will happily take all sixteen waking hours of your day.

Obviously, that is an overgeneralization, and TZ’s noplace proves that exceptions to this rule exist. I think for most founders, though, it’s a good rule of thumb, and I’m inclined to follow this advice myself unless I come across new ideas that change my mind. For now, consumer social does not seem like a nut I’m equipped to crack (without funding).

One more insight is that just a few months before I attempted to launch Hockey, a similar product launched on the same campus at Columbia. Sidechat was pitching the same idea, and they even acquired Yik Yak around the time I ran my experiments.

What’s worse is that I heard rumors that Sidechat was paying users up to $1 for every friend invited to the app, uncapped. That’s not a marketing strategy I could compete with. Social has become a different game since 2014, and people spend crazy amounts of money to acquire an initial user base.